IN THE DOGHOUSE

Hound Lodge, once home to 100 of Goodwood’s hunting dogs, is getting a glorious new lease of life.

One hundred years ago, Hound Lodge’s human occupants were somewhat outnumbered by the house’s other tenants: 100 lively, snuffling hounds, kept for the hunt and noisy enough to be quartered well away from Goodwood House. In 2015, the tables are being turned as the flint and brick house, opposite the Kennels, undergoes a major restoration programme. It’s a thrilling comeback for the handsome building, which will now be dedicated to humans – although they’re very welcome to bring dogs. And in a nod to the past, two imperious stone hounds will greet them when they walk through the restored doors.

The story of Hound Lodge goes back to the 19th century when Goodwood’s hounds were lodged in the elegant magnificence of the Kennels, a fine classical building in flint by architect James Wyatt. Finished in 1787, it remains one of the best-loved smaller buildings on the whole Goodwood estate.

“It was a classic English country house scenario in which the animals were far more important than the humans,” laughs the architect of Hound Lodge’s refurbishment, Ptolemy Dean. Indeed, the first Duke of Richmond bought Goodwood House and Park in 1697 precisely so that he could hunt in neighbouring Charlton, which for many years was the most fashionable hunt in the country. To this day, its name is commemorated in Goodwood’s Charlton Hunt restaurant at the racecourse.

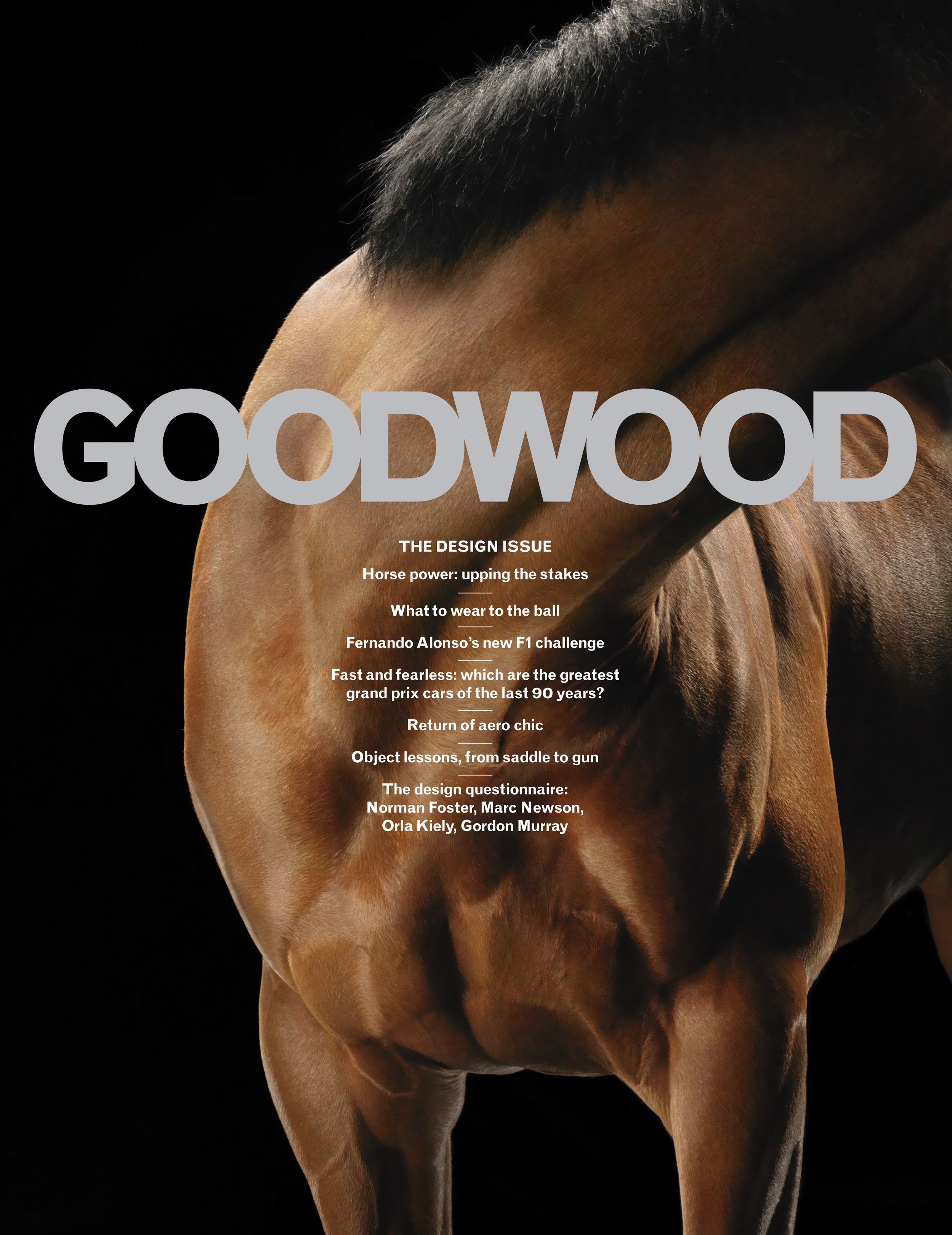

In the 18th century, Goodwood was enlarged, its grounds arranged in powerful axes in the grand Classical manner by master architect Wyatt. “Part of his landscape for Goodwood was an important plantation called the Valdoe Coppice which makes a formal access point,” says Dean, pointing at the 1760s map in his Georgian offices near London Bridge. The architect, well known for appearing in two BBC series, Restoration and The Perfect Village, is a specialist in bringing tradition alive, and his refurbished Hound Lodge will rekindle the old glory days of hunting and hospitality.

Goodwood’s classical landscape would have evoked the mythic images created by artists such as 17th-century painter Claude Lorrain, and have had due regard to symmetry, proportion and elements arranged for maximum enchantment. Wyatt, a Grand Tourist himself, went to Italy to soak up Classical and Renaissance influences, then brought them back to Britain to give the growing country house fashion a historic spin. His axes were put in, with Goodwood House at the apex. Hunting became the picture; the landscape the canvas. The hounds capered across this extraordinary landscape, pretty as a picture and delighting visitors to the house.

Over time, horse racing became more fashionable than hunting, and in 1880 the Kennels were converted into stables. The young bucks converging on Goodwood for a weekend’s sport turned their attentions to the horse rather than the hound. With their tails between legs, the beagles left their grand home in 1880. So where would the poor hounds go? The answer was provided by nearby Petworth House, which had a more modest lodge for its hounds – indeed, it still exists to house the hounds of the Chiddingfold, Leconfield and Cowdray Hunt. Goodwood decided to build one for itself. “I have a lovely vision of squires on horseback, saying, ‘we need one of those’,” says Dean. Bounced out of Wyatt’s glorious Palladian kennels, they transferred to a flint-and-brick building with tiled roof. Although more modest, it has the kind of country cottage look that is now fashionable. The hounds lived downstairs, while on the second floor were the steward’s quarters – no doubt the poor chap lived a noisy life. There is a photograph from the 1880s showing stern fellows and their hounds in front of a cottage-style garden, now being replanted by gardener Tom Stuart-Smith.

As the years progressed, Hound lodge became neglected, marginal, occupied by a car park. Something has to be done and for Dean, there was one key architectural issue: that Hound lodge cut across Wyatt’s classical composition of Goodwood’s wider estate. “Frankly, Hound lodge was a bit of an imposition on the Wyatt scheme,” says Dean.

Thus, Dean is not only restoring the building itself, but also restoring the old Wyatt axis and sight-lines, with a view to making Goodwood whole again. At the back of the building he’s designed a “screen” with a path leading to a courtyard, although it’s grander than the word “screen” suggests: almost like a Gothic folly. The idea, he says, is to create an arcade of flint-and-brick arches and interplay of light and shade, leading the eye to a tantalizing framed gateway. “Go through that gate, and you’ll be plunged into a picturesque world,” says Dean. “It’ll be a lovely surprise to arrive at the entrance of Hound Lodge, then walk out into the courtyard, and the landscape on the other side.” And once more, it will assert Wyatt’s axis by recreating the line through Hound lodge. “Wyatt’s a serious architect, firmly in the Classical post-Grand Tour tradition,” says Dean. “It’s nothing more than he deserves.”

Dean is to clad the building with handsome oak boarding and tiled roof, creating a practical country look. The flint will be remade in lime, which allows the building to age well. Appropriately, the two aforementioned hound sculptures on plinths will have pride of place.

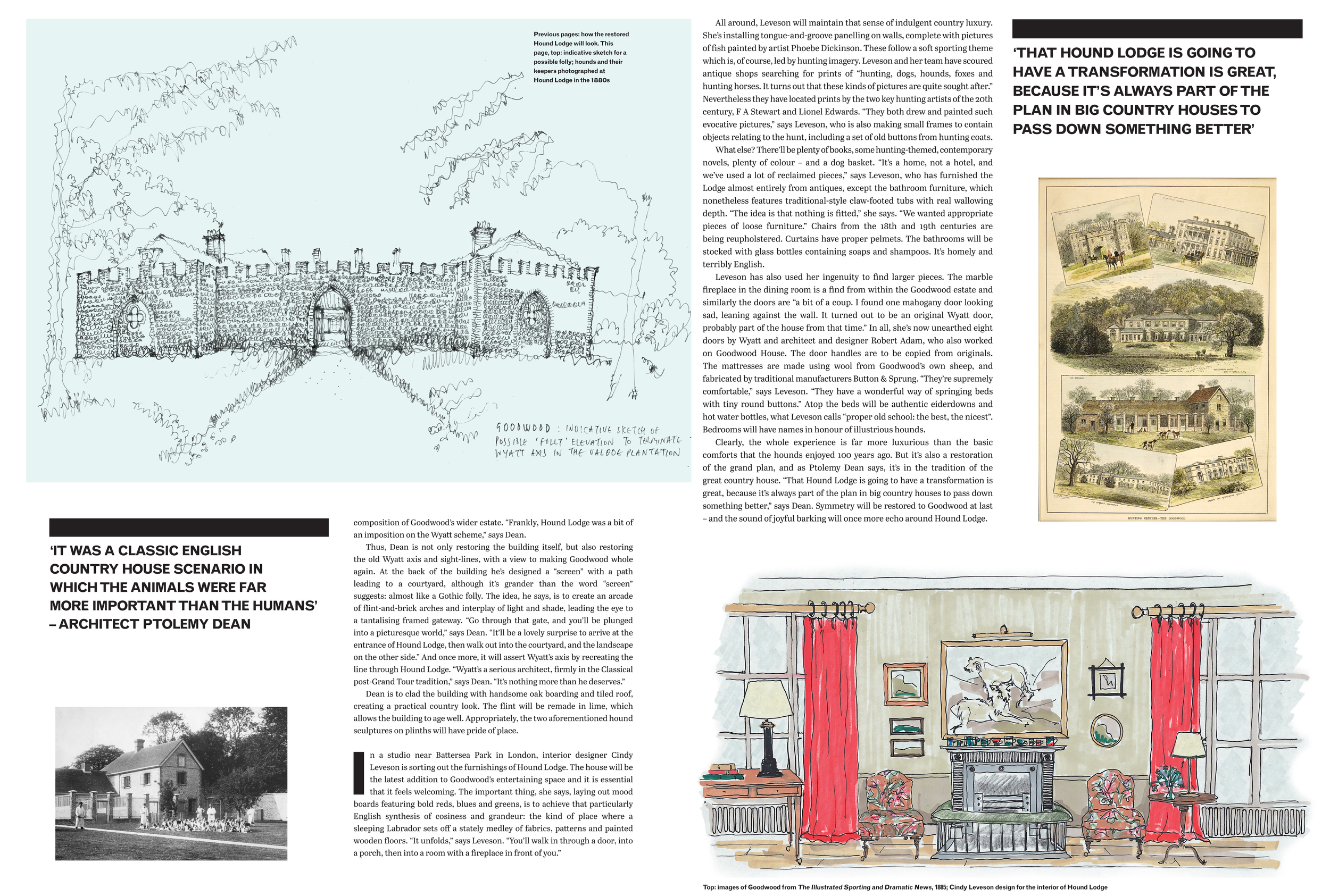

In a studio near Battersea Park in London, interior designer Cindy Leveson is sorting out the furnishings of Hound Lodge. The house will be the latest addition to Goodwood’s entertaining space and it is essential that is feels welcoming. The important thing, she says, laying out mood boards featuring bold reds, blues and greens, is to achieve that particularly English synthesis of cosiness and grandeur: the kind of place where a sleeping Labrador sets off a stately medley of fabrics, patterns and painted wooden floors. “It unfolds,” says Leveson. “You’ll walk through a door, into a porch, then into a room with a fireplace in front of you.”

All around, Leveson will maintain that sense of indulgent country luxury. She’s installing tongue-and-groove paneling on walls, complete with pictures of fish painted by artist Phoebe Dickinson. These follow a soft sporting theme which is, of course, led by hunting imagery. Leveson and her team have scoured antique shops searching for prints of “hunting, dogs, hounds, foxes and hunting horses. It turns out that these kinds of pictures are quite sought after.” Nevertheless they have located prints by the two key hunting artists of the 20th century, F A Stewart and Lionel Edwards. “They both drew and painted such evocative pictures,” says Leveson, who is also making small frames to contain objects relating to the hunt, including a set of old buttons from hunting coats.

What else? There’ll be plenty of books, some hunting-themed, contemporary novels, plenty of colour – and a dog basket. “It’s a home, not a hotel, and we’ve used a lot of reclaimed pieces,” says Leveson, who has furnished the Lodge almost entirely from antiques, except the bathroom furniture, which nonetheless features traditional-style claw-footed tubs with real wallowing depth. “The idea is that nothing is fitted,” she says. “We wanted appropriate pieces of loose furniture.” Chairs from the 18th and 19th centuries are being reupholstered. Curtains have proper pelmets. The bathrooms will be stocked with glass bottles containing soaps and shampoos. It’s homely and terribly English.

Leveson has also used her ingenuity to find larger pieces. The marble fireplace in the dining room is a find from within the Goodwood estate and similarly the doors are “a bit of a coup. I found one mahogany door looking sad, leaning against the wall. It turned out to be an original Wyatt door, probably part of the house from that time.” In all, she’s now unearthed eight doors by Wyatt and architect and designer Robert Adam, who also worked on Goodwood House. The door handles are to be copied from originals. The mattresses are made using wool from Goodwood’s own sheep, and fabricated by traditional manufacturers Button and Sprung. “They’re supremely comfortable,” says Leveson. “They have a wonderful way of springing beds with tiny round buttons.” Atop the beds will be authentic eiderdowns and hot water bottles, what Leveson calls “proper old school: the best, the nicest”. Bedrooms will have names in honour of illustrious hounds.

Clearly, the whole experience is far more luxurious than the basic comforts that the hounds enjoyed 100 years ago. But it’s also a restoration of the grand plan, and as Ptolemy Dean says, it’s in the tradition of the great country house. “That Hound lodge is going to have a transformation is great, because it’s always part of the plan in big country houses to pass down something better,” says Dean. Symmetry will be restored to Goodwood at last – and the sound of joyful barking will once more echo around Hound Lodge.